Brahmaputra is the only river referred to in the masculine; a river that has intrigued travellers and scholars alike for centuries. Over 3000 km long, it is one of Asia’s most awe-inspiring rivers, unpredictable, taciturn and yet responsible for an unusual bridge across three major world religions, namely Hinduism, Islam and Bangladesh, given that it traverses three countries—China, India and Bangladesh—with different names, of course.

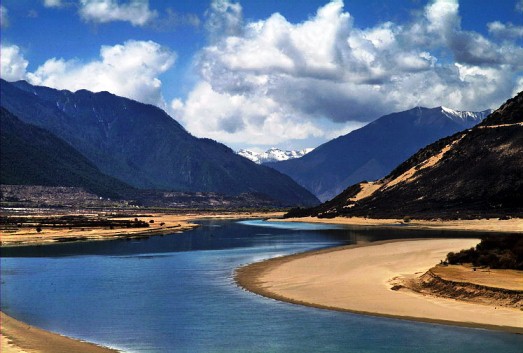

And even as this great waterway, almost a mini-ocean in itself traverses myriad geographical formations, including glaciers, gorges and sand, here’s taking a closer look at this miracle of nature, and a melting pot of human civilisations.

Legend has it…

As per Indian folklore, the creator of the universe, Brahma was deeply smitten with the lovely Amogha, wife of the Sage Shantanu, who he spotted gathering flowers and fruit in the forests of Mount Gandhamadana. But Amogha turned him away in no uncertain terms. Brahma returned home to his abode, dejected.

When the sage heard of this, he learnt that Brahma’s proposition would benefit the Universe, as the child born of them would be great. He requested Amogha to reconsider, but she was firm about the boundaries of her modesty.

So the sage used his divine powers to ensure a miraculous conception and Amogha gave birth to a child with features resembling Brahma, and with a unique shimmering watery form. He was named Brahmakunda and placed him between four mountains. With the passage of time, this water body grew into a lake swelling up to forty miles, resembling the sea. He was Brahma’s son (Putra in Sanskrit)—‘Brahmaputra’.

Traversing territory

The numerous tributaries that feed the Brahmaputra rise in the Himalayan glaciers of western Tibet, near Mount Kailash. Then running east through Tibet, past the mountain mass of Namcha Barwa near the “Great Bend” of the Tsangpo (the main river of southeastern Tibet), they continue their meandering journey through impossibly deep gorges, before turning south towards India. After a gradual descent, the tributaries enter Arunachal Pradesh as the Dibang, Siang and Lohit rivers, which finally merge in the Assam Valley to form the Brahmaputra.

Upon entering Assam, the Brahmaputra becomes braided. The river and its numerous tributaries form the massive flood plains of the Brahmaputra Valley, where the span of the river can reach almost 20 km, making it one of the widest rivers on the planet.

Pilgrims’ progress

Strangely, for a river with such mythological associations, there are only a few centres of pilgrimage along its banks. Perhaps this has something to do with its unpredictable nature that causes great devastation from time to time; perhaps the masculinity of the river stands out in a culture that traditionally reveres the river in the feminine avatar.

But there are exceptions, like the Parasuramkund and the Kamakhya temple of Guwahati, Hajo and the Umananda Temple on Peacock Island. Parasuramkund, on the Lohit River (one of the tributaries), which is associated with the warrior sage Parasurama, attracts millions of devotees who congregate here during the Hindu festival of Makar Sankranti (mid-January) when a big fair is held. Prior to the devastating earthquake that struck the region in 1950, Parasuramkund (or Brahmakund) was almost ringed in by a rocky wall that gave it the appearance of a small lake. The earthquake destroyed this natural dam and today the mighty river roars past a rickety bamboo fence that protects the pilgrims from the fury of the river.

Guwahati, in the river’s middle course, hosts the iconic 16th-century Kamakhya Temple. This is the seat of tantric worship in northeast India and the day usually begins with animal sacrifices to appease Kali – the furious avatar of the Mother Goddess. Hajo, near Guwahati, is the best example of the Brahmaputra’s multi-religious appeal. This ancient pilgrimage centre caters to the spiritual needs of three religions: Hindus, Buddhists, and Muslims.

Just off Guwahati lies Peacock Island. On this stunted hillock in the middle of the Brahmaputra stands the Umananda Temple (16th century) dedicated to Shiva and his consort Uma.

River of mercy…and mercilessness.

Usually–a river is seen as a life-giving force and cradle of human culture, which, in all fairness, the Brahmaputra certainly is. But then, its legacy is way more complicated.

Between June and October, crazy floods are a common occurrence. Deforestation of the Brahmaputra watershed has resulted in soil erosion, increasing the probability of flash floods. This flooding that helps replenish the fertile soil of the river valley is also responsible for great misery. But, when the roads along the river are rendered unmotorable, the river highway of the Brahmaputra provides a welcome respite to the besieged people of the valley, allowing vital supplies to be transported. Perhaps it’s a tribute to the resilience of human nature that the people of the valley have taken this endless cycle of destruction and resurrection in their stride. The floating river ports on the Brahmaputra are symbolic of this spirit.

Crucible of cultures.

Until the 15th century, most people in Assam belonged to non-Aryan ethnic groups, who believed in animism and nature worship. Majuli, near Jorhat, then became the nucleus of the Neo-Vaishnavite movement. In Assam, the proliferation of this movement is generally attributed to the social reformer and writer Sankardeva. In the latter part of the 15th century, he ushered in a socio-cultural renaissance. Humanist in content and popular in form, it was incorporated in literature as well as the arts. This tradition still survives on the island of Majuli. Of the 46 major satras only 26 remain today, most of which date back to the 16th century.

Today, many islands and villages along the Brahmaputra face extinction, but the river also creates new landmasses. The landscape here is in a constant state of flux.

In unorganised settlements along the Sunderbans, where the delta is vast, this does not seem to matter. Every monsoon, the nomadic people shift their temporary residence and are constantly on the move like the river. But in an organised settlement like Majuli, which has been shrinking continuously due to soil erosion, the socio-economic problem of resettlement becomes acute.

For some settlements though this is fatal. Every year, the river swallows a few kilometres of land here, whilst depositing silt on the opposite bank. Many residents of cities like Tezpur, Guwahati and Jorhat have lost their agricultural land and have been forced to migrate to urban areas in search of work due to this.

Ecological impact

The Brahmaputra supports a vast eco-system and the grasslands of Assam are famous for their wildlife, especially the iconic one-horned rhinoceros that has been adopted as a state symbol. Goalpara and Kaziranga are two of Assam’s most famous wildlife sanctuaries.

From Goalpara, the river meanders west towards Dhubri, where it enters Bangladesh. This town is famous for its bamboo trade and floating markets. Traders from Meghalaya and Arunachal float down the river on bamboo rafts, which they take apart and sell here.

The broad river then splits into two channels; the main stream called the Jamuna in Bangladesh joins the Padma arm of the Ganges. Together, they eventually join the Ganges and Meghna rivers and their numerous distributaries to form the Sunderban Delta – the largest and most fertile delta in the world, before flowing into the Bay of Bengal.

The mangrove forests of the Sunderbans are best-known for the magnificent Royal Bengal Tiger. The floodplains are cultivated extensively, both in India and Bangladesh. Other than agriculture, fishing plays an important role in the economy of both countries.

Rising sea levels due to global warming pose a major threat to the ecosystem of the region and many islands are now partially submerged. But then, it is for mankind to intervene and restore what it has disturbed.

While we can go ahead and debate animatedly over which river has had the maximum impact on India’s civilisation and socio-economic demographic what a great pity it would be if the Brahmaputra were to rival the Ganga for pollution.

Written by: Kalyani Sardesai

Leave a comment